Gravity Battery - well, well, well...

A couple of moths ago I was given a week to prepare a fifteen minute technical presentation on something that I’ve recently been working on. I figured this would be an opportunity to develop and pitch an idea I’ve been pondering - can a well (oil and gas) be economically converted into an energy storage device?

The Concept

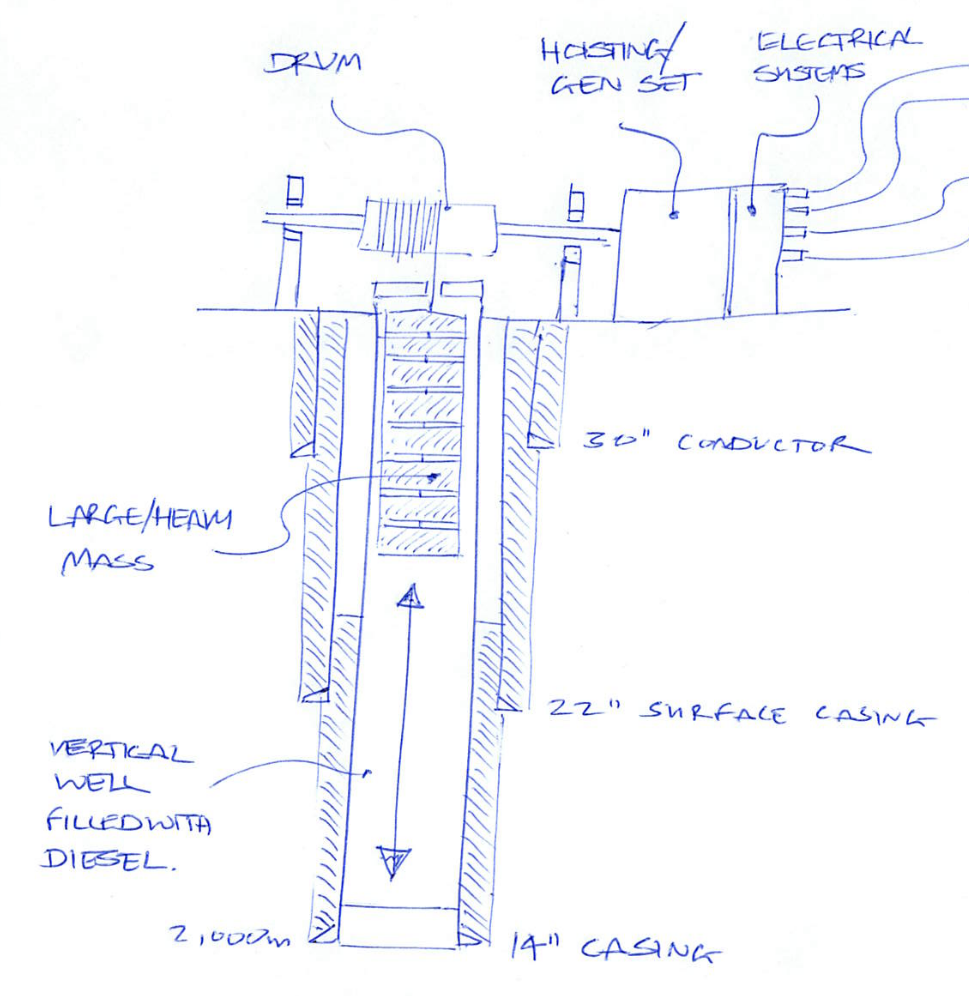

The concept is nothing novel - hoist a mass up to create some potential energy and let gravity convert this into electrical energy via a generator.

The commerciality of this concept is currently being tested by Gravitricity (with support from Huisman) and Energy Vault amongst others, but with so many wells in the oil and gas industry coming to the end of their production lives, plus a glut of highly specialized equipment and personnel idling from the current downturn in the oil and gas industry, I felt that there’s a potential opportunity here to economically address the energy storage problem in the transition to a sustainable energy system.

Wells Concepts

Four concepts were considered in this exercise:

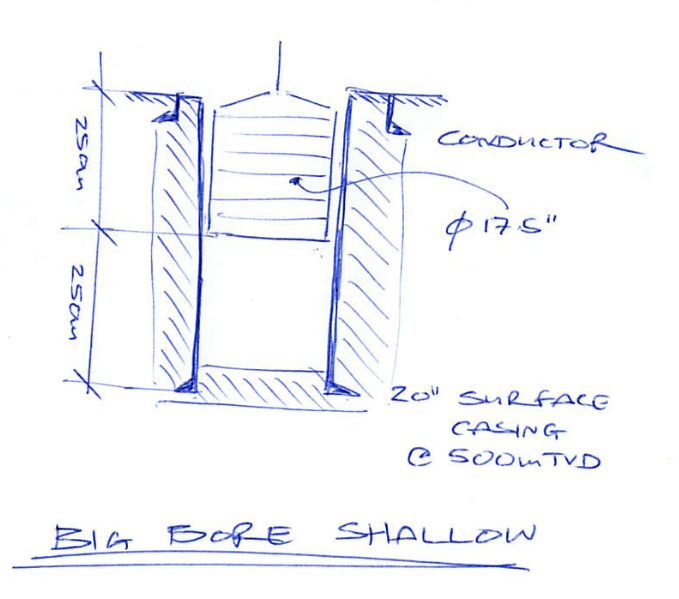

Big Bore Shallow

Since many wells are deviated (they are not vertical from top to bottom) and assuming that we want a (near) vertical well for our gravity battery, it’s reasonable to assume that for many existing wells we’d only be able to utilize the shallow, vertical section of the well bore.

This limits the stroke of the battery, but similar to the Gravitricity concept, this can be offset with a larger diameter mass. The assumption here is that we can re-purpose the surface casing with a drift diameter of 17.5 inches. We’ll assume that the surface casing can be utilized down to 500 meters True Vertical Depth (TVD) and that we’ll use a mass length of 250 meters, leaving 250 meters of stroke.

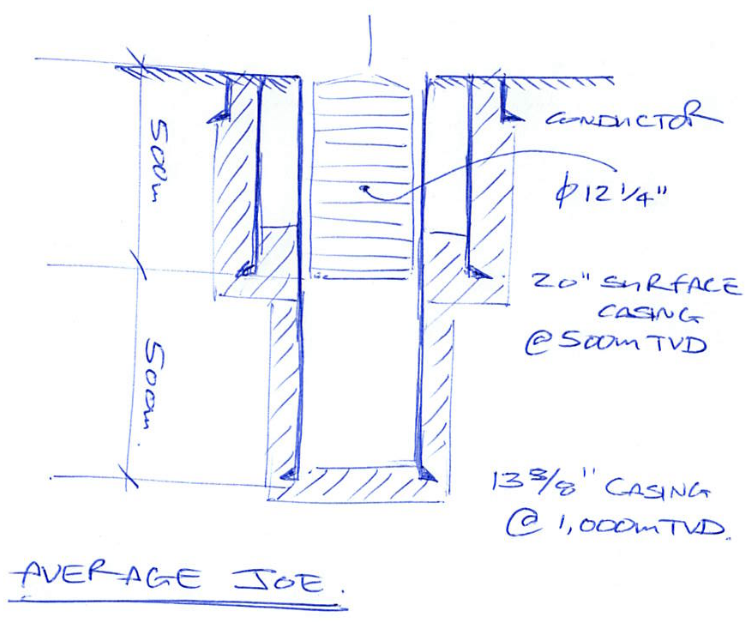

Average Joe

Some existing wells may be vertical down to the intermediate casing shoe, especially exploration wells that tend to be drilled vertical.

In this scenario, the drift of the well bore is assumed 12.25 inches with a depth of 1,000 meters TVD and we assume that the mass length is 500 meters with a stroke of 500 meters.

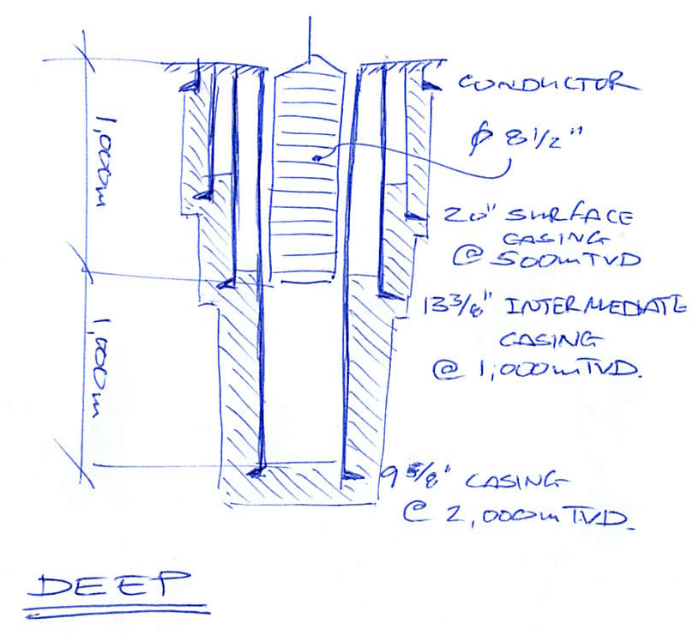

Deep

Although it may be feasible to re-purpose some deeper existing wells, we also need to consider a couple of options in the event that we want to drill new wells with the specific purpose of energy storage. We’ll discuss why we might want to do this later.

Here we assume that we have an 8.5 inch drift down to 2,000 meters TVD, with a mass length of 1,000 meters and a stroke of 1,000 meters.

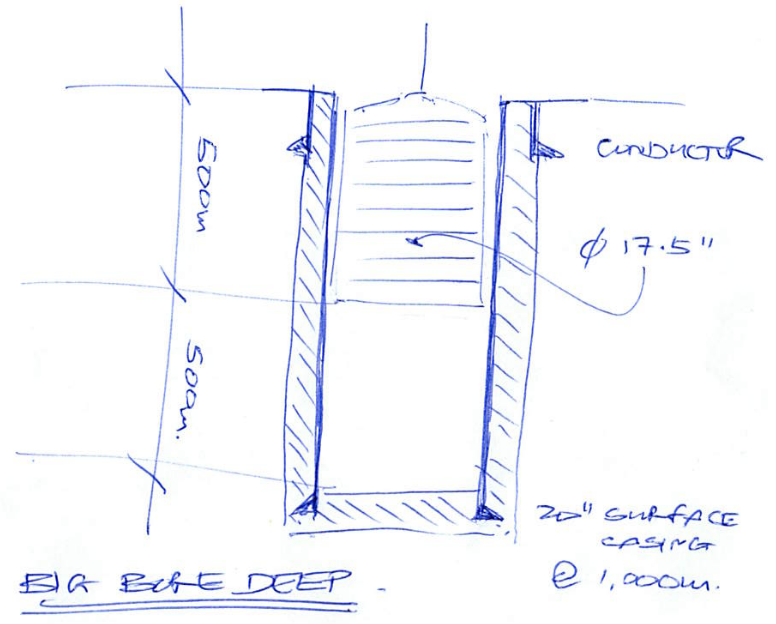

Big Bore Deep

With unlimited Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) we might consider drilling a large diameter well bore for as deep as possible (constrained by the drilling rig if we’re committed to using existing oil and gas equipment and services).

So in this scenario, we assume that we can set the surface casing down to 1,000 meters TVD with a drift of 17.5 inches allowing for a 500 meter mass length and a stroke of 500 meters.

Power and Capacity

Now that we have some scenarios we can start doing some math - using Python of course. First off, let’s get a feel for the order of magnitude of power and energy storage capacity we might expect from these batteries and put these into some context.

| Concept | Peak Power (MW) | Capacity (MWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Big Bore Shallow | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Average Joe | 0.14 | 0.36 |

| Deep | 0.27 | 0.69 |

| Big Bore Deep | 0.29 | 0.73 |

Let’s compare this to a Tesla Powerwall which has a capacity of 0.013 MWh and a peak of 0.007 MW (or 0.005 MW continuous). The gravity well offers approximately 10-50 times the capacity of a Powerwall, but what’s special about gravity batteries is their capability to ramp up to peak power output in a very short time and to be able to maintain that output through the entire discharge cycle.

What’s also interesting in the above results is that the peak power output of the Deep and Big Bore Deep concepts (around 250 kW) is aligned with the genset currently being trialed by Gravitricity and Huisman.

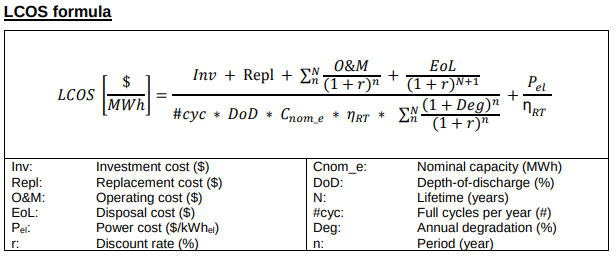

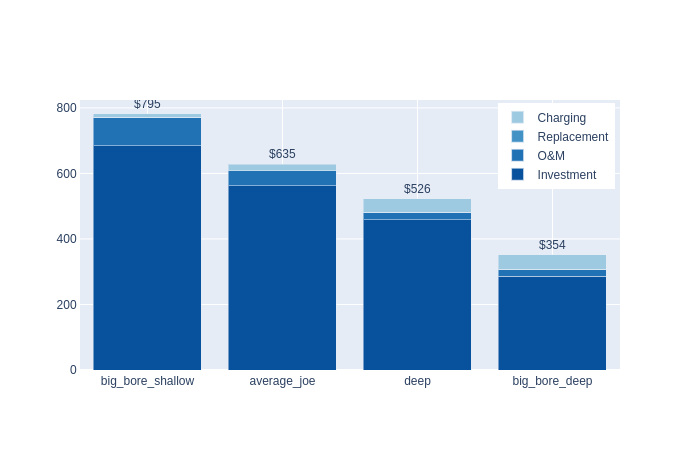

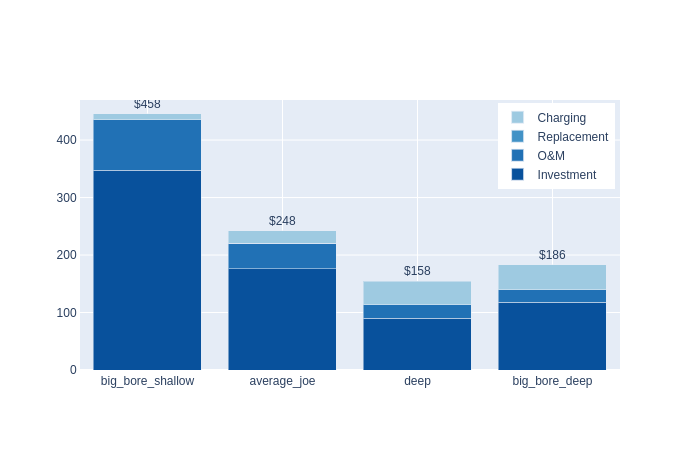

Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS)

Of course, it’s not fair to only compare the outputs of different batteries without considering capital and operating costs. Fortunately, there’s a methodology for doing just that, which has been used on the four wells concepts to determine the US Dollar cost per MWh of storage capacity. Of course, this is easily done using Python code, a link to which is provided at the end of this post.

We’ll consider two scenarios, first including costs for drilling new wells and then considering the cost of re-purposing existing wells.

Drilling new wells

Having coded up the LCOS formula, the parameters for the gravity well concepts need to be input - this was done by creating the Python dictionary below:

params = {

'G': 9.81,

'density': 7800. - 830., # assume well diesel filled and take net density kg/m3

'costs': {

'casing_20': 800., # $/m

'casing_13': 400., # $/m

'casing_9': 250., # $/m

'steel': 650., # $/tonne

'rig_rate': 40_000., # $/day

'location_construction': 100_000., # cemented, run-off collection, cellar

'surface_equipment': 100_000., # winch, variable speed drive and switch gear

'replacement': 40_000., # cost of replacing variable speed drive after 25 years

# 'replacement': 0., # if life of VSD is 25 years and lifetime is 25 years

'operating': 10_000., # estimate of annual operating cost

'disposal': 100_000., # abandon well and location

'power': 50., # $/MWh taken from report $/MWh

},

'depth_of_discharge': 1., # able to utilise all stored energy

'discount_rate': 0.07,

'lifetime': 25, # years

'cycles_per_year': 730, # same assumption as report

'annual_degradation': 0., # it's mechanical so assume no degradation

'round_trip_efficiency': 0.85, # same assumptions as report

'peak_power_duration': 2.5, # same assumption as report

}

Ideally, this would be converted to a YAML input file or similar so that parameters for a range of different battery solutions could be batch processed and the results compared.

Below are the results for drilling a bespoke gravity well storage device (the y-axis unit is $US/MWh):

For comparison, lithium-ion comes in around $US/MWh 350-400 with compressed air around $US/MWh 300, meaning that only the Big Bore Deep concept is commercially competitive. Intuitively, this makes sense if you consider that the cost of a (simple) well is proportional to to the time it takes to drill and the depth of the well (which dictates the cost of equipment and consumables). The take away here is that size matters - a new well needs to be deep while maintaining as large an internal diameter as is feasible.

Re-purposing existing wells

What makes re-purposing existing wells an attractive option is that much of the CAPEX has already been paid for by the (oil and gas) project that funded the original well and that a chunk of the cost to re-purpose the well can be allocated to Abandonment Cost (ABEX).

Below are the results for drilling a bespoke gravity well storage device (the y-axis unit is $US/MWh):

Here we see that except for the Big Bore Shallow concept, re-purposing of existing (oil and gas) wells looks to be commercially competitive if suitable near vertical donors can be found.

If you want to compare these results to the Gravitricity concept, they commissioned a study by Imperial College London Consultants that is available on request.

Context

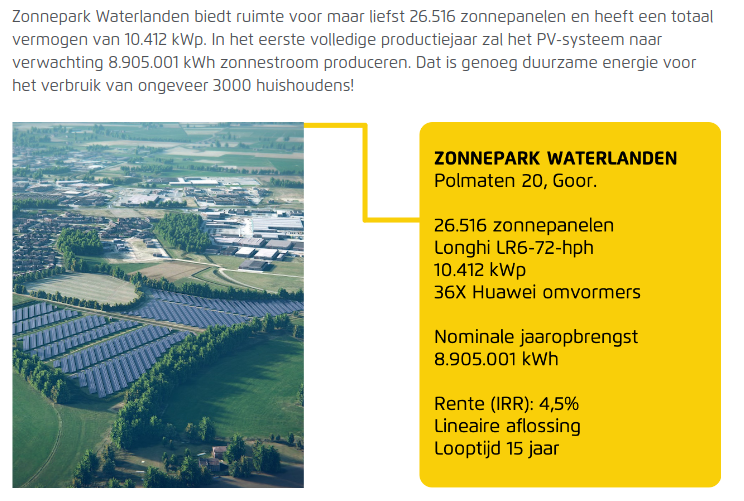

We’ll wrap up with a typical scenario where gravity wells might be utilized to smooth out the production of electricity from a solar PV farm, taking some specifications from a decent sized Zonnepanelen Delen (a crowd sourcing solar PV organization in the Netherlands) project.

- A decent sized solar PV project in the Netherlands generates about 24 MWh capacity per day.

- Let’s assume that we allocate one third of this production to storage (e.g. for supplying electricity through the night or meeting peak demand) - required storage capacity is therefore 8 MWh.

- Assuming we drill Big Bore Deep type wells with a capacity of ca 0.7 MWh, we’ll need a total of 12 wells.

- Assuming a cost per well of $US 1.6 million, a total investment of ca $US 20 million is required for energy storage.

Clearly, the cost of producing electricity is far less than the cost of storing electricity. They’re expensive, but drilling and operating gravity wells has some advantages:

- The oil and gas industry has experience of drilling close to densely populated areas (especially in the Netherlands), which means that storage can be located very close to where it’s needed, negating the requirement for additional infrastructure.

- With 12 wells being operated, there’s redundancy if a well fails and maintenance can be performed offline.

- Each well can be operated close to peak efficiency - some wells can be designed to run at higher discharge rates while others can be designed to cater for background rates.

Conclusion

Under certain scenarios, a mechanical gravity battery operated within a well looks to have potential as a competitive concept for energy storage and warrants further investigation.

As usual, feel free to download the code: